A PATERNITY TEST FOR SCIENCE

Ron Londen

THINKSTOCK

Nothing is more obvious to today’s world than the accomplishments of the scientific enterprise. Modern science has improved the lives of almost every person on this planet. The only people not substantially helped are those forced by cultural, political, or economic constraints to live with a shortage of science.

Given this winning streak, it’s easy for the devout naturalist to declare final victory of “rational” science over “superstitious” religion. Yet the victory lap can only come at the cost of ignoring some inconvenient facts.

If we mark the birth of modern science to Nicolaus Copernicus (he published On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres in 1543), then the whole thing is currently rounding the corner toward its five-hundredth birthday. A date for a “naturalist” consensus in science is harder to pin down but could arguably go back to at least the mid-1800s, if not earlier. Before that—and since—great scientists have emerged from perspectives of faith.

Isaac Newton is often cited as the most important scientist of all time, even though he was profoundly religious. Newton and dozens of other “science fathers” pursued their work precisely because of their faith convictions, not in spite of them.

Theology was once celebrated as the “mother of sciences.” It’s pretty clear Mom has been kicked out of the house, starting with the whole Galileo episode and ending, perhaps, with Darwin. Far less obvious is the role theology—specifically, Christian theology—played in the development of modern science.

By most objective measures, Europe made a lousy candidate for the birthplace of science. Survival was at the top of everyone’s to-do list for the millennium following the collapse of the Roman Empire. Certainly cultures other than Europe had more advanced civilizations and plenty of resources, but fundamental barriers in their worldview inhibited the emergence of science in those regions.

Historians of science have examined this era extensively and produced lists of factors that were essential to Europe’s arrival at the leading edge of modern science, which I will synthesize as four essential attitudes. Each perspective is not only allowed by Christian theology, but demanded by it.

A linear view of time

Aside from the “religions of the book”—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—the vast majority of cultures throughout human history have taken a deterministic, cyclical view of the natural world. “Nature as rhythm” has immediate intuitive appeal to anyone who plants crops, watches the sky, or sleeps at night. From this, ancient cultures invented vast, complex systems picturing the universe in a constant cycle of life, death, and renewal. In many cultures the perspective led to a fatalistic view that inhibited scientific inquiry.

For several reasons, Christian theology completely rejected this cyclical view of nature. First, of course, is the biblical account of creation ex nihilo—creation out of nothing. A second rejection of a cyclical view was more nuanced and theological: Christ went to the cross “once for all,” the Bible states.1 For Jesus to endure the cross repeatedly was an intolerable idea and kept Christendom permanently off the treadmill of a cyclical worldview.

An orderly view of nature

A biblical outlook on nature can help avoid two perspectives, either of which would hinder the development of science. The ancient Greeks had both in some measure.

The first attitude about nature that is corrosive to science is organismal, viewing nature as a single, living whole. Aristotle taught the heavens were perfect, divine, living, with Earth as the corrupt bottom—what Galileo called “the sump where the universe’s filth and ephemera collect.” The most extreme version of the organismal view is pantheism—the worship of all creation—that is common in many pagan religions. Buddhism has strong organismal leanings that tend to frown on pointing too many scientific instruments at objects of worship. Monotheists, instead, are called to be responsible stewards of creation, a duty sadly observed far too often in the breach. As G. K. Chesterton observed in Orthodoxy, the Christian view is that nature is not our mother but our sister.2

Those not choosing to worship nature might decide instead to deny it. Again, the Greeks got involved, with their transcendent “Platonic forms.” Plato taught that whatever we observe in nature is a cheap knockoff of a higher “form,” which is the really real deal. So why study the world around us?

When it comes to denying the reality of the world, the Greeks couldn’t hold a candle to India’s culture. The Hindu concept of maya insists our senses are bombarded with false knowledge. The world we perceive is a complete illusion, which presents a challenge for funding science research.

A reverent view of God

Anyone who read Greek tragedies in high school probably concluded that the gods were a bunch of bitter, jealous, vindictive, capricious little jerks with a god complex — except for the part about actually being gods. If your world is run by those kinds of deities, why bother studying it? You’ll just get on their bad side and end up gouging your own eyes out.

The Christian perspective on the universe is shaped by a different view of God. In the gospel of John, Jesus is introduced with the phrase “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.”3 The “Word” here is a Greek term signifying “divine reason,” “mind,” or “wisdom.” The Christian expectation is that a rational God would produce a rational world.

Even with its roots deeply sunk into monotheistic soil, the Islamic perspective on God risked undermining confidence in a rationally accessible world. Judeo-Christian theology sees God’s attributes as, in some respects, a constraint — such as the biblical promise that God cannot lie. But early Islamic theologians tolerated no such limitation on the absolute and arbitrary power of the Almighty. So what is for the Christian an abiding confidence in divine character is to the Muslim at best a policy of the moment. God does not lie, unless he changes his mind.

A confident view of man

British biochemist Joseph Needham gives account of contact between Jesuit missionaries and Chinese scholars in the eighteenth century. When told that scientific developments in the West indicated an underlying, orderly nature to the cosmos, the Chinese thinkers simply refused to accept the news. The problem wasn’t a belief in an ordered nature, but rather the idea that mankind could possibly begin to understand it.4

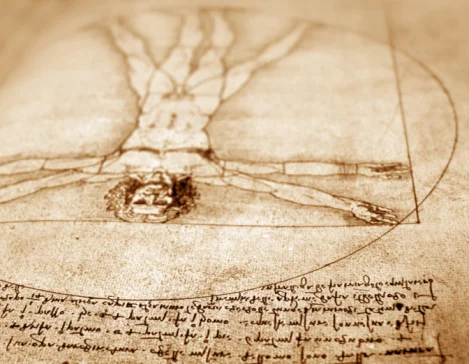

Einstein said famously, “the most incomprehensible thing about the universe is that it is comprehensible.” But to the biblical theist, that comprehensibility isn’t the least bit surprising. Mankind is a product of nature, but not merely that. Created Imago Dei — in the image of God — mankind is both innately curious and uniquely qualified for discovery.

If theology, then, was not indeed the “mother of sciences,” it was at least a talented midwife.

(Adapted from Chapter 2 of The God Abduction.)

1 1 Peter 3:18.

2 Chesterton, G. K., Orthodoxy, (Westport, Conn., Greenwood Press [1974, c1908]),88.

3 John 1:1.

4 R. Stark, (Random House, New York, ed. 1st ed., 2005), pp. 24-26.