Optimism and the search for ET

Ron Londen

A recent study released by Penn State University revealed that a search of 100,000 galaxies has found no evidence of highly advanced civilizations in any one them. For interesting reasons, that study probably amounts to less than meets the eye. Or, if a recent internet kerfuffle is to be believed, maybe more.

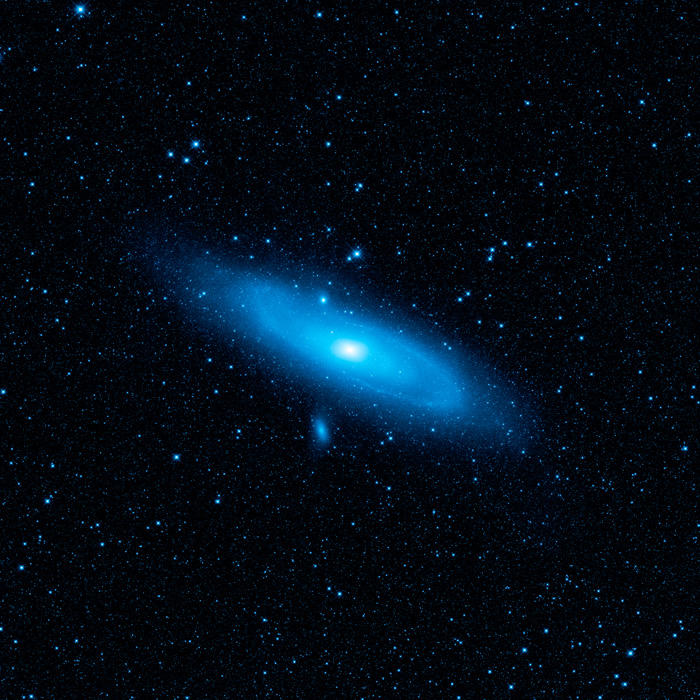

The study by Penn State’s Center for Exoplanets and Habitable Worlds surveyed an enormous set of observations by NASA’s WISE (Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer) satellite, examining 100,000 galaxies. They were looking for galaxies whose total energy output exceeded expectations. Such a high output of energy (heat) might be a sign of an advanced civilization that colonized most of that galaxy. They found nothing that fits the bill.

“Our results mean that, out of the 100,000 galaxies that WISE could see in sufficient detail, none of them is widely populated by an alien civilization using most of the starlight in its galaxy for its own purposes,” said Jason T. Wright, an assistant professor of astronomy and astrophysics at the center, in Science Daily’s coverage of the story. “Either they don’t exist, or they don’t yet use enough energy for us to recognize them” (emphasis added).

There’s the rub. They were looking for a galaxy that is so completely filled by an advanced alien civilization that most of their starlight is repurposed for its use. In other words, if this technique were used in some distant galaxy to detect us, it would certainly fail. Given such limitations, why bother with this kind of study? The answer may not lay so much in science as in philosophy.

One of the tenets of philosophical naturalism (the positive assertion that no god exists) is the so-called Copernican Principle, better described as the Principle of Mediocrity. Simply put, it is the idea that our planet is not an exceptional place within the universe. Yet that is not a scientific discovery; it is a philosophical assertion — and not a new one.

“There nowhere exists an obstacle to the infinite number of worlds,” the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus wrote. “In all worlds there are living creatures and plants and other things we see in this world.”1 The notion that intelligent life is common throughout the universe is fundamentally an optimism about other worlds that stems from a pessimism about ours, and the idea had legs. Our world, the thinking went, was nothing special, just another punk planet. There’s got to be a bunch of them littered around the universe.

The height of this extraterrestrial optimism was not ancient Greece, but rather the modern West, from the eighteenth century through the middle of the twentieth. For many, it was a given that nearly every star hosted life, with dozens of the leading thinkers of the nineteenth century waxing breathlessly about Martians, Venusians, Jovians, and even Solarians — citizens of the sun. (It’s a dry heat.)

Now we know better, at least about our neighborhood. There are good reasons to believe life is much, much rarer than earlier expected. But it’s important to note that the expectations about extraterrestrials were driven primarily by philosophy. That’s why we need scientific inquiry; we have to balance our presumptions with observed facts. But in this case, it was a philosophical presumption — drawn from naturalism — that led us astray. The example is important because, rather than serving as an inoculation against philosophical presumption, naturalism turns out to be just another infection.

And today, philosophical presumption is driving the conversation.

Last week, Slate posted “God’s Chosen Planet,” an 1,800-word exploration of why “creationists” are “afraid” of finding extraterrestrial life. To his credit, writer Mark Strauss tried to summarize the positions of The Discovery Institute, the Seattle-based think tank that advocates Intelligent Design — meaning that he at least read it before criticizing. Not everyone does. But the tone of the piece leaves the impression that Slate might be paying its writers by the snide.

At any rate, it’s one thing to accuse The Discovery Institute (or anyone else willing to entertain the idea of an Intelligent Designer) of rooting for one side in the search for ET. Guilty as charged. But it’s quite another to do so without breathing even a syllable that the issue cuts both ways — that naturalists have a philosophical dog in the hunt for ET. Of course they do. If not, why scour 100,000 galaxies looking for an alien civilization so huge and so advanced that we can detect their leaving the lights on from trillions of miles away?

The past few decades have seen a boom in the search for extraterrestrial life. Hundreds of planets outside our solar system have been identified and the number constantly grows. In addition to this study’s galaxy-based survey, other teams have proposed searching on a planet-by-planet basis, looking for life-chemistry, or industrial pollution, or even city lights on alien planets.

That’s why we do science. The answer is not for one side to accuse the other of a bias that they clearly suffer as well. The answer is to keep looking. I suspect the results will be fascinating either way.

(Portions adapted from chapter 2 of The God Abduction.)

Photo: NASA W.I.S.E. satellite

1 (Epicurus, Letter to Herodotus).Cited in Are We Alone?, by Paul Davies, 1995, pp. vii-viii.